At Her Majesty’s Pleasure

The first decades of the nineteenth century were particularly arduous for the free settlers of Van Diemen’s Land. Although general supplies from Port Jackson were reasonably reliable (weather permitting), there was an urgent need to be self sustainable.The one thing the new colony lacked however was a labour force. The New South Wales colonial government had - since settlement - utilized the manpower of British and Irish convicts to great effect and a petition was put to the local Tasmanian authorities to fund a similar program on the island. After gaining coronial consent a penal settlement, under the governorship of George Arthur, was commissioned. Situated on land occupied by a small timber station in 1830, it wasn't until the first English and Irish convicts landed in 1833 that the station became a stockade. Of humble design and constructed by tradesmen convicts, the prison facility become "home" to petty felons and hardened criminals alike. Over the next seven years it grew to house over 1000 inmates and became regarded as the strictest of all British Prisons - the infamous Port Arthur (pictured). Like it or not the free settlers had their workforce when the penal authorities decided to rehabilitate as many of the shorter term inmates as quickly as possible. Some prisoners, particularly those with an agricultural background, were indented to the free settlers whilst others became members of supervised work gangs. |

| Thomas Chard Inmate: 4968 Period of Servitude: 1842 – 1857 Port Arthur prison’s inmate records [1] tell us that Thomas Chard was initially assigned to such a gang working in the central highland’s Victoria Valley region. Next he laboured for Mr Frederick Vigar [2] of Woodsdale, finally completing his probation period at the end of 1843. To this point of time his prison record was unblemished. 1844 saw Thomas indented to a chap named John McPhail, who in the 1842 census had been listed under the category of “Shopkeeper / Retail Dealer”. McPhail, a married man with two children, managed a business in Bridge Street Richmond owned by Mr William Wise [3]. When Thomas joined the household as a labourer he shared duties with two fellow convicts, another male labourer and a housekeeper - an Irish widow named Honora Daly [1]. |

| Freedom, as a convict, was a relative concept as Thomas found out in the beginning of 1845. For “leaving the township (presumably Richmond) on a Sunday and being in a public house” he was brought before a magistrate, charged with misconduct, and sentenced to six days of hard labour [1]. By May of the same year a further public house misdemeanour was reported by McPhial. This time Thomas received five days hard labour. Honora Daly’s prison record shows that shopkeeper McPhial had also reported her for corresponding “public house” misdemeanours. Clearly now a “couple”, Honora and Thomas were courting trouble with the parole board. |

| John McPhail and Thomas Chard finally parted company in August of the same year. This time the convict was reported for being “absent without leave” and the judge sentenced him to 10 days imprisonment with hard labour. By March 1846, still in Richmond, Thomas found himself labouring at Cartwright farm, property of Peter McCullock [4]. A change of employer however did not improve his behaviour as he was once again on report to the authorities for misconduct. Even though they were now working apart it may well have been the case that Honora was not a good influence on Thomas, or visa-versa. The remainder of this year saw him move from property to property working just weeks at each. 1847 was a momentous year. From February to June, Thomas found himself at Jerusalem Station (now Colebrook) organizing the deployment of new convict arrivals into work gangs. Obviously seen by the authorities as a positive step in his rehabilitation, Thomas was given his ticket of leave on the 12th October. |

|

Tasmanian Convicts Index courtesy of Archives Tasmania.

|

Tasmanian convicts were indexed according to the name of the ship upon which they arrived. The image above is a portion of the page pertaining to Thomas Chard (HMS Somersetshire). It informs us that inmate 4968 was a Protestant who could not read. He was 5 foot 3¾ inches tall with a round and chubby visage. He had dark brown hair, grey eyes and a dark brown beard. Under the heading of trade he was listed as a “farm labourer complete”. |

| Honora Daly Inmate: 17018 Period of Servitude: 1843 – 1852 Born Honora Carthy about 1804 [5] in County Cork, "Nora" was the eldest daughter of Irish catholic parents Mary and Patrick. There are no surviving Irish records available to establish her family’s origins but her convict record does provide some information [6]. She was a mother at 21 bearing five children - two of them girls (Honora and Mary) to a Mr Daly. In 1836, with the food crisis in Ireland beginning to take effect, Nora - now a widow - together with her younger sister Ellen, were apprehended by the Cork constabulary for stealing 4 sheep belonging to a Mr Sherlock. Having no mercy the judge sentenced the sisters to 10 years - and transportation. Nora along with her sister and two daughters sailed from Dublin on May 10th 1843 aboard HMS East London. All four arrived in Van Diemen’s Land on the 21st September. Although Nora’s prison record shows that her brothers emigrated to the United States of America, no evidence could be found to confirm this fact. Nearly one year after she had arrived, Nora was classified as a 2nd Class prisoner (29th March 1844) and was indented as a housekeeper to a Richmond store trader named John McPhiall. Six months later that classification was downgraded to 3rd Class (presumably as a result of a misdemeanour reported by McPhiall). Nora's tenure in the McPhiall household was shaky. Her out-of-hours carousing with fellow convict Thomas Chard was testing the patience of the dour Scotsman as twice in 1845 she was "absent without leave". The second of these instances, which may have been the occasion of her sister’s wedding to John Durrant, landed her in Richmond Gaol for a stint of one month's hard labour. Nora's personal circumstances probably did not help her state of mind, for, upon arrival in Van Diemen’s Land, the housekeeper had been separated from her younger sister and her two daughters had been placed under government care in the Hobart Town’s Queens Orphans School [7]. Luckily for daughter Mary, her aunt’s marriage provided her with a home and family guardian. The authorities did not allow the elder Honora to accompany her much to mother Nora’s dismay. The following year saw a shift in her fortunes as McPhiall - just as he had done with Thomas Chard - cancelled her employment contract, and her indenture continued as a servant to a Mr Ellis of Richmond. Sadly her penchant for the “devil drink” continued with her employer having to report her for being drunk on duty in April of 1848. For this demeanour she spent 3 days in Richmond’s gaol cells. It was on the 31st of October this same year that she was granted her ticket of leave. One of the conditions of a ticket of leave was that a convict must reside in a given district of the colony and for Thomas and Honora, Richmond was that district. Clear of the misdemeanours of the past twelve months Thomas and Honora were given permission to marry by the authorities on December 4th, 1849. A blind eye was obviously turned to a bigamous union by the authorities for the records show that Thomas’ first wife Mary was still alive in Devonshire at the time. Did this crime really matter given that Thomas would never be allowed to return to his homeland? |

|

Images courtesy of Archives Tasmania.

|

Marriage of Thomas Chard and Honora Daly

This image combines the two official documents relating to the marriage of these two convicts. The upper portion is an extract [8] from the Port Arthur official record books listing convicts applications for permission to marry. It is of interest that this entry for Thomas and Honora was dated retrospectively as the actual marriage had been performed a few months earlier. The lower portion – the official certificate [9] – albeit displaying incorrect ages for both parties states that on New Year’s Eve 1849 Thomas Chard, a dealer and Honora Daly, a widow were married by the Reverend Arthur Davenport at St Luke’s United Church of England and Ireland. Neither bride nor groom could write evidenced by signing with their respective marks. Of interest were the witnesses, namely John Durrant and Jane Kean; both being fellow convicts from England. In 1845 Durrant had married Honora’s younger sister Ellen, also Richmond residents. The Reverend Davenport took charge of the parish in the beginning of 1847 and stayed at Richmond until 1851, before becoming Archdeacon of Hobart. |

|

Courtesy of the National Trust of Australia (Tasmania).

|

St Luke’s United Church

The Parish Seat of Richmond, Tasmania

Built by convicts from locally quarried stone, St. Luke's stands practically unchanged today as it was when consecrated in 1834 - the foundation stone being laid by Governor Arthur. The original timber framework inside the church was constructed by James Thompson, a convict who was granted his freedom as a reward for his work. Now the Anglican church (pictured here by Don Stephens in 1963), this square, stern, massive building, today, stands sentinel over the quiet Tasmanian township of Richmond. A far cry from the busy prosperous village that witnessed the constant columns of convict gangs [10] in their clanking irons. |

|

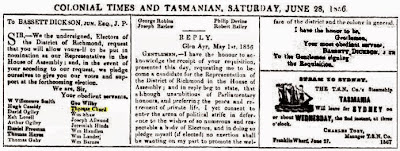

So, at the age of 40 with his 46 year old Irish bride at his side, Thomas embarked on a new phase of his life with his ‘ticket of leave’ (sentence expiration) being officially pronounced in the local newspaper the following year. Described as a “dealer” on his marriage certificate it’s anyone’s guess what that entailed, but whatever he was dealing, he was doing it in the Richmond district. It would seem that the couple’s lifestyle stabilised in the ensuing five years as his presence is noted at a political rally held at the Star and Garter Hotel in 1856 when his name appears among a published list of persons (pictured below) pledging their support for Richmond’s prospective representative in the Tasmanian House of Assembly. |

| This may well have been a fortuitous pledge as just barely a year later, on October 12th 1857; Thomas was given his 'Free Certificate'. Whether Bassett Dickson had any influence on this decision is worthy of contemplation? With their freedom secured Thomas and Nora should have had no further association with the authorities but, this was not the case as in mid 1859 Thomas was once again arrested. This time the crime was far more serious than stealing livestock - being charged with indecent assault of a young Richmond girl. On November 5th 1859 he was brought before Hobart Town’s Supreme Court Magistrate. Fortunately he was acquitted. |

|

Sketch by James Watt Beattie, 1838. Courtesy of Tasmania Museum and Art Gallery.

|

The trial details regarding the Court's case against Thomas Chard are published (left) all over the island colony. The Supreme Court of Tasmania situated in Hobart Town was the first judicial building [11] in all Australian colonies. Erected in 1824, this historic site (right) was the stage for Thomas Chard's trial. |

|

Now just shy of his sixtieth birthday, Thomas is arrested for larceny for the second time in his life. This time the alleged theft is a pair of boots. Now a misdemeanour clearly regarded as “petty” (larceny under the sum of £5), it was still reported in the newspaper on the 8th July 1869. Again Thomas Chard is acquitted of the crime. In August of the following year Honora Chard died, her death being registered [13] in Richmond. Although no recording was located for the fact she was most likely buried there, with her husband being her only family present to witness the occasion. |

| The Star and Garter Hotel, Richmond. Mentioned in this 1869 newspaper article as the scene of a crime, the Star and Garter (Inn) Hotel, located on Bridge Street, Richmond was a local public house [12] from 1841 to 1874. The image (inset), photographed by Claire Baker in 1995, is of a shopfront renovated from the original colonial building. |

| Interestingly Thomas’ first wife Mary had died in Wellington, Devon in the March [14] of the same year – a fact that would have been completely lost on James’ father. Thomas survived another three years but died [13] alone and penniless, being interred by the state in a pauper’s grave in Hobart Town’s Cornelian Bay [15] cemetery. |

|

Image courtesy of Archives Tasmania.

|

Thomas Chard’s Death Certificate

Registered in The Hobart General Hospital, Thomas died of Phthisis Pulmonalis (aka Tuberculosis). There may have been a post mortem on the body given the significant gap between Thomas' date of death and the certificate registration date |

| THE DOCUMENTS OF FREEDOM |

| A Ticket of Leave A ticket of leave (TOL) was a document given to convicts when granting them freedom to work and live within a given district of the colony before their sentence expired or they were pardoned. Ticket of leave convicts could find employment or be self-employed. They could also acquire property. Church attendance was compulsory, as was appearing before a Magistrate when required. Permission was needed before moving to another district and 'passports' were issued to those convicts whose work required regular travel between districts. A Conditional Pardon A Conditional Pardon is a document that freed convicts from servitude, conditional upon them never returning to the United Kingdom or Ireland. Original copies of the pardons were sent to England and duplicates remained in Australia. Copies were also given to convicts as a proof of pardon. |

| JUVENILE CUSTODIAL DETENTION Although the British Government had been shipping convicts to Botany Bay for many decades, by the mid 1840’s they were prevailed upon by the New South Wales authorities to desist. This left Lord Howe Island and Van Diemen’s Land as the only remaining destinations for the continuing dispersal of Parkhurst boys. There was a solution to the problem however as Paul Buddee writes [16] in The Fate of the Artful Dodger, “This matter was of considerable concern to Sir James Graham the Secretary of State for the (British) Home Office, which controlled Parkhurst. He wrote a letter [17] to the Parkhurst Prison authorities in 1842 proposing that although Australian mainland states would no longer receive convicts, they would however be grateful to receive trained labour.” As a consequence “Parkhurst boys were divided into four classes (transportation categories): free emigrants; colonial apprentices (ticket-of-leave boys); an orderly but unreliable group (third-class boys); and boys with sentences over ten years (fourth-class boys), and to submit this proposal of 'free' trained labour with his recommendation to his colonial counterpart Lord Stanley." Although some boys were sent to New Zealand (which was at this time under the jurisdiction of New South Wales) and Western Australia, the majority landed in Van Diemen’s Land and the penal settlement of Port Arthur. The juveniles however were housed in a separate compound on Point Puer peninsula. |

|

Sketches by N. Remand (c 1840) courtesy of the University of Tasmania [18].

|

Point Puer Boys Prison

Drawing of Port Arthur (foreground) and Point Puer peninsula (background). The key to the sketch is as follows; 1. Workshops. 2. Boys barracks. 3. Chaplain’s quarters. 4. Commandant’s quarters. 5. Sawpits. 6. Exempt room. 7, 8. Military guardhouse. 9. Gaol. 10. Exempt room. 11. Gaol. 12. Superintendent of gaol’s quarters. The rather naive drawing [19] (below), held in the Tasmania Museum and Art Gallery is believed to be the work of one of the juvenile inmates of the time. Point Puer (the name originating from the French word for “boy”) was a prison for juveniles. Built in 1834, across the harbour from Port Arthur, it was to become the second reformatory built exclusively for juvenile male convicts in the British Empire. Whilst high building standards had been set for Port Arthur, this was not been the case at Point Puer. Most of the construction [16] was done by the boys and built more for utility than for comfort . The barracks for 700 boys were 27 meters long and 24 meters wide doubling as a dormitory at night and classroom cum church during the day. The small compound - as sketched above - was located on the windy Opossum promontory (pictured) and described by the then Commandant William Champ [17] as “a wretched, bleak, barren spot without water, wood for fuel, or an inch of soil…” . Modelled on Parkhurst Prison standards, but dressed rather differently (as seen in the sketch opposite), Point Puer was renowned [20] for its regime of repressive discipline and harsh punishment . The authorities were of the view that it was not just 'young innocents' being incarcerated. Many of the boys had been 'schooled' [21] in the inner city slums of London and were accomplished villains . Their seven and one half hour working day [23] began at 5 am with carting wood and general labouring work. The boys were also schooled in trades that included carpentry, sawing, tailoring, stone cutting, painting, shoemaking, baking, nail making, blacksmithing, boatbuilding and gardening. This physical activity was evenly balanced with school work and religious instruction. From time to time there were breaches of discipline amongst the boys involving bullying and numerous occurrence of violence being incited by adult ‘ticket of leave’ overseers from Port Arthur. One such instant [21] resulted in the murder of said overseer in 1843 by two of the boys. |

| James Chard Inmate: 17088 Period of Servitude: 1845 – 1847 Hardly a Christmas Day to remember but it was on this day in 1845 that James Chard and his fellow Stratheden shipmates were escorted ashore in Hobart Town to enter the prison processing system. Called the Assignment Scheme, a plan whereby convict labour was allocated specified heavy duty tasks seen as integral in the establishment and development of the new colony. Tasks like tree-felling, quarrying, road-making and coal-mining were fine for adult workers but could not be assigned to most boys as they were too small and underfed. Instead they were registered [23] in the Probation Gang System. After working for two years in a labour gang and, if they were well-behaved, convicts received their 'probation pass’ (ticket of leave) which meant they could then work for wages. For James, although his life had been turned upside-down, there was much to be thankful. Courtesy of Her Majesty’s Parkhurst discipline and his willingness to co-operate and learn James could now read and write and had attained a trade as a painter - these achievements being documented [1] at the time of his arrival in the colony. He was indeed also fortunate that his last year at Parkhurst was included in his probation period meaning that he had only to endure one year at Point Puer. His ticket of leave was granted on January 20th 1846 and he was indented to work in Hobart Town. |

|

Tasmanian Convicts Index courtesy of Archives Tasmania.

|

| The image above is a portion of the page pertaining to James Chard [1]. It informs us that inmate 17088 was a Protestant who could read and write. He was 5 foot 0¾ inches tall with high shoulders. He had a round face (head) displaying a fresh complexion with no facial hair and no spectacles. His nose, mouth and chin were regarded as small. Under the heading of trade he was listed as a painter. |

|

James Chard’s life continued without complications and he was recommended for a conditional pardon on December 1st 1846. Sadly however the administration process was delayed as there were two tumultuous years when controversy raged over the failure of the Convict Probation system and a constitutional crisis caused Lieutenant-Governor, Sir John Eardley-Wilmot (who was responsible for the system's inception) to be stood down from office. As seen in this extract (left) from Hobart's Colonial Times Newspaper [24], it was not until November 30th 1847 that his pardon was granted. Having served almost 2 years in the colonial penal system, the seventeen year old James Atkins Chard was a free man. He was also a "new" Australian. |

| THE BIG QUESTION |

| Did father and son reunite? In answer to the question put to James Chard on how he came to Australia, the family legend [25] goes something like this:- ‘Back home in Devonshire he had stolen some eggs and the family decided to send him to relatives in Tasmania to avoid facing court and ending up with a black mark against his name’. So at the first telling of this ‘story’ (probably to his future employers or his wife in the late 1850’s), James knew he had a family member in Tasmania – his father – and that he was also a convict. In 1845, when his son arrived, Thomas was labouring at Cartwright Farm in the Richmond district and was lucky to be outside a gaol cell given his spate of misdemeanours during the previous months. Did he know of his son’s arrival? Most likely not. During the period of his servitude, did James know of his father’s existence in the colony? Yes possibly. Unless he absolutely detested his father, human nature would suggest that if at all possible the son would try to make contact with the father. Ticket of leave constraints meant that this could not have happened before November 30th 1847. We also know that James arrived in mainland Australia early in January 1848, which leaves only the month of December 1847 for a possible reunion. Although father Thomas was given his ticket of leave on 12th October 1847 he was restricted to the Richmond district. As James must travel through Richmond to exit the colony, did he break his journey to see his father? Only God knows. |

References

|